published in Polish Music Newsletter, April 2004, Vol. 10, No. 4

Simply, as Chopin would have liked his music to be played. His letters explained it, and his students and students of students in Paris transmitted his tradition. Reviews on his Parisian concerts in elegant salons and also at the Salle Pleyel demonstrate his success with beautiful work on the pedals for musical expression, the clarity of his polyphony, the delicacy of his touch, and his occasional violence at the piano when his health would permit it!

Chopin was a classic, nurtured by Bach and Mozart. He did not like bluff and ostentation, and each note had a purpose. The intimate Nocturnes, Preludes, and Mazurkas should be played for yourself, wrapped in your solitude, and not for the gallery. Express the angry and dramatic Preludes with violence, but a contained violence: they are the lava that erupts from inside. Nothing in Chopin is written to impress, to dazzle. Everything comes from his inner being, and must reach your inner being. Some Mazurkas are joyful; they are the remembrances of a happy youth in the country. With the Ballades tell the ancient stories that have been transmitted since the beginning of time. Their myths have nurtured our poets. The Polonaises express strength, pride, and also deep sorrow and revolt. They are amazing, coming from such a fragile being as Frederic Chopin, gifted, however, with a tremendous nervous energy and a visionary temperament.

WHAT HAS BEEN YOUR EXPERIENCE WITH POLISH STUDENTS?

As a university professor, I travelled to Europe to recruit very good students for my Foreign Student Scholarship Program. Two of them were Polish, Anna Kijanowska and Anna Rutkowska, both from the Wroclaw Music Academy. The solidity of their preparation impressed me particularly, as well as their dedication, ambition, hard work, and musicality. Anna K. has received her DMA from the Manhattan School of Music, and Anna R. recently performed at Carnegie Recital Hall. We are constantly in touch, I have a "soft spot" for them, and they express so much gratitude for my teaching and care. There is no doubt that the bond derives from Chopin and Poland! I think that what they got from me is greater clarity in their playing, more refinement in details, and that comes from my French upbringing. We went through a complete, well balanced repertoire including the prodigious Samuel Barber Sonata that Anna R. recently performed in Poland with great success: it was at the time my husband and I were concertizing and lecturing for Polish audiences.

IF YOU COULD OFFER A FEW SUGGESTIONS FOR PLAYING CHOPIN, WHICH ONES WOULD YOU CHOOSE?

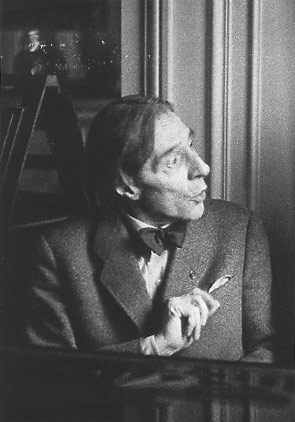

I would suggest a legatissimo approach to the keyboard, as taught to me by my teacher, Alfred Cortot, when I was a girl. Cortot was a wonderful Chopin interpreter, by tradition and by nature; he had a foot in the nineteenth century, and his teachers had heard Chopin play in Paris, a very direct link. On top of that, Cortot was a born poet—he also played Schumann as if hallucinating. As a teacher, he was superb! I will select some of the qualities that Cortot developed in me and his students: very even and agile fingers, rather flattened for better tone, flexible hands and joints (Chopin always mentioned "la souplesse" to his students), a minimum of percussion, except in the Polonaises. It is not well-known that his Etudes are more difficult to play than those of Liszt. Why? Because the whole Etude treats one problem (for example thirds, sixths, or octaves) without interruption, whereas Liszt mixes the problems, permitting you to rest your hand and arm from one problem to another: opposite muscles work in alternation. An article from the 1920's by Nouneberg includes Rubinstein's comment that his fingers did not permit him to play Chopin's Etude in Thirds!

Your technique has to be accomplished and refined so as to allow you to play effortlessly and elegantly, without forcing. The fortissimo is never to be harsh, the sound must remain that of the Italian bel canto, which Chopin so greatly admired, as in Bellini's music. In his letters he writes that Liszt's flamboyant pianism and virtuosity shocked him. In the presence of Franz, one can only imagine Frédéric closing on himself like a flower at night.

PLEASE SHARE YOUR EXPERIENCE WITH 19TH CENTURY PIANOS.

In his Paris flat, Chopin had an Erard grand piano and a Pleyel grand. It is said that he composed at the Pleyel. In the 1830's the center of the pianistic world was Paris. Virtuosos from all over Europe flocked to the French capital, and French piano-making was flourishing. Pleyel and Erard pianos represented advances in construction and tone that contributed significantly to the pianism of the great romantic composer-virtuosos. In 1821 Sebastien Erard patented his mechanism "double échappement," the repetition action. This piano is not only light and responsive, but also powerful. Besides repetition, Erard decided to use a metal reinforcement in the framing to allow increased tension. (I wonder if Erard received his inspiration from Liszt, whose technical novelties required stronger and stronger pianos: he was known to break strings at concerts, and Parisian cartoons depict him as a victorious gladiator among decimated pianos!) The 1881 Erard grand I used for my recording differs little from the Erard of Chopin's last years.

Chopin preferred to perform on a Pleyel piano when he was feeling healthy and in good form, because he had to "create" his sound as he said. A Pleyel is less brilliant than an Erard: it is mellow and warm in tone, and can be played in perfect legatissimo, Chopin's fan, Jane Sterling, would have described it as being "like water," which amused Chopin. Double thirds can be taken at an incredible speed, in comparison to what is produced, for example, on a Steinway which, being heavier, can hold the pianist back. Also its booming basses make it difficult to maintain clear contrapuntal lines. It is easier to sing a Chopin melody on French pianos, which are mostly treble oriented.

The Yale University Collection of Musical Instruments owns the 1881 Erard grand piano, never rebuilt, which I used for my concert and my recording, and an 1842 Pleyel grand which I used only for my concert. It is very similar to the last piano Chopin owned (now at the Palac Ostrogskich in Warsaw). Although it needs some work, nobody dares touch it, so it maintains an authentic 19th-century sound!

|

|

|

Alfred Cortot

|

|